Éamon de Valera in Charlotte: The Cradle of American Sinn Féin

News

29 April 2020

Mary Elizabeth Lennon

M.A Irish Studies, New York University

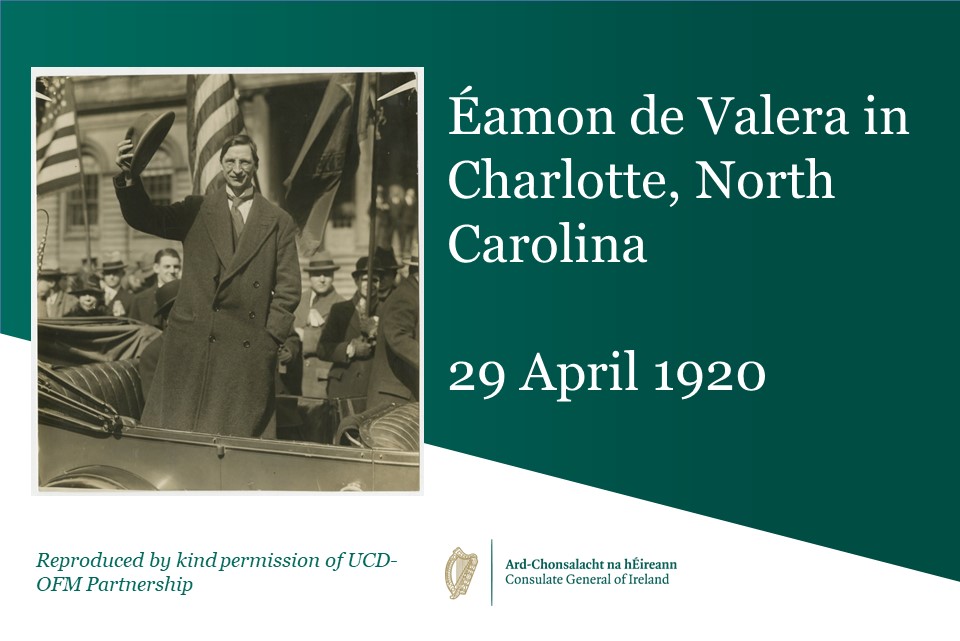

On April 29, 1920, Éamon de Valera arrived in Charlotte, North Carolina to speak on behalf of the Irish Republic. Known primarily in the United States as a veteran of the 1916 Easter Rising, de Valera came to Charlotte as President of Dáil Éireann, the elected representative of the Irish people. His visit to Charlotte was part of a larger, nationwide tour meant to rally support and funds for Irish independence.

De Valera’s goals in the United States were to seek official recognition for the Irish Republic, raise money for his government with the sale of bonds, and consolidate American sympathy for the cause. He failed at this first goal, but wildly succeeded at the second two. He raised over $5 million for Dáil Éireann and captured the public’s attention for the duration of his visit.

De Valera toured the South extensively in April of 1920 to varied results. In cities such as Charleston and New Orleans, he was greeted with parades and welcomed by members of local government. Meanwhile, Alabama Governor Thomas Kilby announced that had he the power, he would deport de Valera. His speech to students at the University of South Carolina was canceled altogether due to outrage from prominent alumni.

Much of the hostility to de Valera and Sinn Féin in the United States came from the American Legion, a recently-formed organization of veterans of the First World War. The Legion repeatedly accused Sinn Féin of supporting the German war effort and criticized their “disloyalty” to Britain at a time of war.

The Hornet’s Nest Post of the American Legion stated their opposition to any appearance by de Valera, adopting resolutions expressing that “no good can come of such a speech” and appointing a committee to take the matter before the city commissioners. In reporting on these resolutions, The Charlotte News accused de Valera of “siding with the enemies of the Allies and of the United States.”

Local chapters of the Officers of the Great War, Woodmen of the World, and American Officers’ Association joined the protest, submitting a formal request to Mayor McNinch asking that he bar “speakers of de Valera’s type.” The Mayor, despite declaring de Valera unwanted and personally unwelcomed in Charlotte, conceded that he could not legally prevent him from speaking publicly.

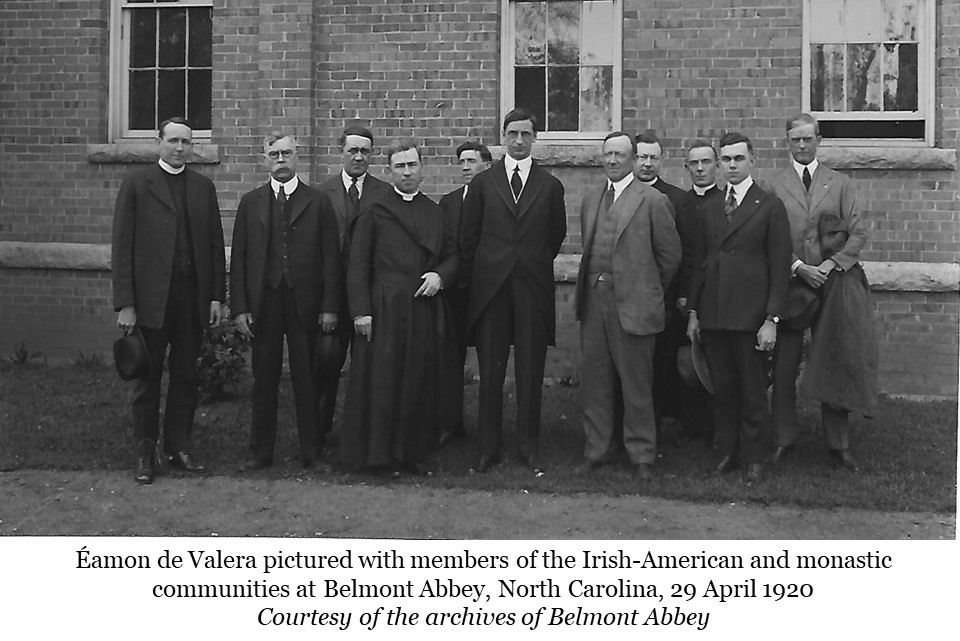

This is not to say that de Valera was wholly reviled in Charlotte. Before his speech at O’Donoghue Hall, de Valera and his team were welcomed at Belmont Abbey College, a Catholic institution with a long Irish history. De Valera was also supported in Charlotte by the Knights of Columbus and the Friends of Irish Freedom. When The Charlotte Observer and The Charlotte News reportedly refused to publish details of de Valera’s meeting, members of the Friends of Irish Freedom produced and distributed advertisements in the city.

De Valera and his team were explicit in their desire to appeal to prominent Southern Protestants and non-Catholics on their tour. Reverend Dr. J.A.H. Irwin of Belfast toured the South with de Valera, reminding Southerners that they spoke on “a civic rather than a Catholic basis.” Colonel T.L. Kirkpatrick, a Protestant lawyer and former Charlotte mayor, was initially recruited to lead the local chapter of the Friends of Irish Freedom. Katherine Hughes, organizer for the Friends of Irish Freedom, also focused her efforts on recruiting women and Jewish members of society to the cause.

Hughes was impressed by Charlotte’s passion and dedication: “The Irish are the ‘Tar-Heels’ of Europe,” she wrote, “this means they never give up their fight.” She praised the city’s rapid organization for de Valera’s visit, calling Mecklenburg County “the cradle of American Sinn Féin.”

Liam Mellows, another 1916 veteran and prominent member of de Valera’s advance team, also noted Charlotte’s revolutionary history:

“This place is in Mecklenburg County, famous in American history for its ‘Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence’ of May 20, 1775, which antedated the Philadelphia Declaration by more than a year. Mr. de Valera should not fail to refer to it, since it will mightily please the Charlottians [sic], who are very proud of their famous Declaration, and in the many controversies that have raged over it they have fought bitterly for it.”

Indeed, one Charlottean wrote in defense of de Valera’s visit, with a strong reference to the Mecklenburg Resolves: “If de Valera be denied a hearing at Charlotte… then the people of Mecklenburg should meet at that famous corner, where their sacred tablet is buried, they should dig it up, load into a hearse, and take it to the cemetery and bury it deep, for all that it represents is dead and forgotten.”

In Charlotte, de Valera wrote that he hoped “to dissipate some of the smoke clouds by which the British seek to hide the true Irish question from fair minded Americans.” His speeches in the South focused on educating the public on Ireland’s relationship with Britain. In the wake of the First World War, de Valera hoped to capitalize on the fierce Americanism that dominated public discourse. He often utilized imagery of the American Revolution to do this: “Now the case we bring here to you to plead, is a very simple case. It is nothing more than the case of Washington and his comrades in 1776.”

Despite the initial frenzy surrounding the visit, de Valera’s time in Charlotte can be considered a success. 500 people gathered at O’Donoghue Hall to hear Irwin and de Valera speak. In the wake of the tour, North Carolinians raised up to $16,000 for Dáil Éireann. Liam Mellows wrote that “everything passed satisfactorily in Charlotte,” while de Valera reflected succinctly, “Charlotte meeting-- fairly good.”

Charlotte was the penultimate stop on de Valera’s tour of the United States. It is one of the best examples of both the hostility and the enthusiasm he faced from the American public. De Valera’s American education in political rhetoric is illustrated in his statements to The Charlotte Observer: “All I ask is a fair hearing—that Americans do not judge the case of Ireland until they have heard that case presented by Ireland’s official representative.”

Mary Elizabeth Lennon is a native of Charlotte, granddaughter of Irish immigrants, and a recent graduate of New York University’s Irish Studies MA program. She will continue her research in Irish-American history at the doctoral level at Fordham University this fall. Mary Elizabeth was scheduled to speak at an event marking the centenary of Éamon de Valera’s visit to Charlotte at Belmont Abbey College this spring. Due to Covid-19, the event will be rescheduled for the fall.